This old article has recently been translated into English by my former colleague Ragnar Næss. Probably he found it still to be of some relevance after 44 years…

Blichfeldt, Jon Frode. In Broch-Utne, B.(red):”Fra ord til handling. Pedagogisk aksjonsforskning i utdanningssamfunnet».(«From words to acts. Pedagogical Action Research in Educational Society”) Scandinavian University Press 1979

We imagine a discussion between two researchers, A and B, where A represents traditional research in the social sciences, and B works in action research. The discussion is presupposed to be made in a congenial spirit. I hope that the dialogue will reveal how both see themselves in their daily work as researchers.

On taking a Stand

A: Why action research?

B: Why research at all? Why do you do research?

A: Me? Basically I believe it has to do with a wish to get a deeper understanding of an area, get into it, understand and explain it. Maybe a dream about finding the final and fundamental truths about human nature and human activity.

B: You think that it is possible to find fundamental traits, maybe laws, regarding relationships between humans?

A: Why not? We have advanced quite far in the natural sciences and the social sciences are young. But we already know a lot even if very much remains. And we don’t have the same possibilities of making experiments with humans

B: But would you have liked to be able to do it?

A: No, I think that we must have some clear borders here. Humans have a quite special place among living things. But we may also learn quite a lot from experiments with animals.

B: But experiments with and on humans do exist, don’t they?

A: Not without their consent. That is, possibly with the exception of cases dealing with people who have particular problems whom one wants to help to a better life.

B: Then your dream is not only about the pure knowledge, but also on the possibility to help people?

A: Clearly! Maybe for most of us there is also the wish to find solutions to concrete problems, to help where it is needed. This is also an important impetus for our work.

B: Then your research results should also be useful. You hope that they will be used?

A: Of course. Maybe it is not so easy to realize what is useful in the first place, but we assume we work for the common good. But you are tricking me into answering. I was the one who asked why you did action research – and you did not answer but started to ask instead.

B: Well, maybe action research is more about questions than answers. But clearly, in the same way as you I am interested in understanding how things hang together. I want to understand, and I would like to help people to get a better grasp of concrete problems. I would like to contribute to developments that I believe are the right and important ones.

A: You say “that I believe are right and important ones”. You then use the research in order to promote your own points of view, or particular theses, or maybe political points of view?

B: I presuppose that we do not discuss party politics. Possibly I would rather use the expression “values”. Through my work I would like to contribute to the realization of certain values.

A: You do not answer my questions. I believe that research must be free and unbound. If you – as you say – already in advance presuppose some values – this will colour and determine your research work. You are then not objective, and I doubt that what you do can be called research.

B: I thought that this discussion belongs to the past. Now listen – a short while ago you said that you hoped that your own research could be useful, you wanted to contribute to the solution of concrete problems. I believe it is not unimportant how your results are being used? As far as I understand the question is not whether research is connected to a value-based context or not. If it does, then research is used, and is useful for somebody. If this is so, you may choose to shut your eyes to this fact, or not.

A: That was a little aggressive. I believe that our task as a researcher is to present analyses, and then it is the task of the politicians to decide what they will do with them. And the analysis must be done on a value free and objective basis. If this is not so, as a researcher you end up as a politician. The questions you ask and the answers you get then do not reflect an objective reality but reality as you yourself want it to be. Research becomes a political means, a tool.

B: I believe that this last point is right – and I believe it applies to us all –also your research (I still presuppose that we are not talking about party politics). And I presuppose that it actually is used in concrete practice. But I believe that it is important to distinguish between two points here: that is the contexts that all research is part of and on the other hand the methods we use in our work. I believe that you confuse neutrality and the rules of proper discussion. None of us can be neutral or value-free. We do not live and function in a social vacuum. But we try to adhere to the rules of proper discussion. But the question of what methods we choose remains. For me the fundamental value is to contribute to people’s ability to have a possibility for understanding, changing and defining their situation. The so-called objective or neutral researcher often defines in detail his or her methods and procedures in advance – no free room for action is left. And after this a definition of reality is presented and the investigation is presented as a proof: This is how it is. I believe the chances of abuse of power is just as big given such methods. You risk strengthening forms of organization in which a few people with power, experts and leaders, define the majority.

On Use of Methods

A: All the same my impression is that your position has a weakness because of your extensive use of so-called soft methods. You do not to any degree employ methods that have been tested according to validity and reliability. That means that you to a great degree must rely on discretionary methods. The more you are guided by discretionary methods, the more your collection of data will be coloured by the values you want to promote. And then you get the answers that you want.

B: The last you say we always want to evade. But I believe that the dangers you see in my approach to an even greater extent exists in your own approach. In your approach you typically propose a hypothesis. And then you as best as you can construct an instrument that you can use in an experiment. You confirm or reject your hypothesis. Your instrument may be a questionnaire with answer categories defined in advance. Yes, I believe it will often be like that. It is possible to maintain that what you get out of such an investigation – what you call data – is given in advance, that is, you have already chosen them in accordance with the character of the hypothesis that you already have proposed. “Data” means what is “given”. In this kind of investigation one should rather talk about “capta”, “what is taken” (Spencer-Brown 1969). You force reality- and the respondents – into the pattern that you have constructed.

A:But if you are to be able to work with larger selections, which is necessary if you are to be able to draw general conclusions, then you must have a common structure. In order to apply statistics to your data, this is also a prerequisite. And isn’t it only by such a procedure that we get to know how reliable our results are?

B: probably it is useful to look at the genesis of social research in the US after the war, approaches that in many ways have been mainstream by us in Norway. Many indicators indicate that social research has developed in a direction indicated by the development of data technology. To an increasing degree one has been looking for questions and themes that are fairly simple and transparent in the handling of which data technology can be useful. Very much of the so-called research from which multitudes of assumed neutral reports emerge lack a sufficient discussion of basic problems and presuppositions that express human behaviour and relations (Clarke 1972). They produce “theories” without theory and meaningless heaps of numbers that provide the basis for bureaucratic decisions in ministries, universities and the big corporations.

A: But this is pure demagogy, emotional loose talk! You have not provided any sound argumentation for what you hold, let alone any concrete examples about what you say.

B: Ok, but it will take some time. I will try to find examples that show that also ordinary research does not provide a secure basis for conclusions. A recent publication in the social sciences (Sandven 1975) aims at finding a methodological basis for reliable standards for the measure of characteristics and tendencies in reaction patterns in human personality, apparently to produce tests to be used in schools. It is a very comprehensive work and at least three quarters of the approximately 370 pages provide comments on data matrixes and curves. There is very little comment on the theoretical basis for this. Four variables are investigated and measured. The variables are seen as traits of personality. And in at least one of the variables, “coreaction”, the meaning of the term as the author defines it is every kind of action provided that some other human is involved in some way or other, even if only in one’s thoughts. The author arrives at representative samples of something that nearly encompasses everything that exists, and even measures this. Apart from the work itself, I can also provide a more comprehensive comment on it (Blichfeldt, 1976).

I can also mention another example taken from a seminar dealing with the conditions of childrens’ upbringing and life. Here a physician, Petter Viken, interprets and comments on a comprehensive and meticulously executed study of the wellbeing of children in schools (Viken,1973). Wait a moment and I will find the book and show you! I think you must see the curves! This is what he says:

“The pupils get the following question:” Do you have a good time at school?…..Let us take a look at the alternatives for answering. “Always”,”often” , ”sometimes ”, ”seldom” , ”almost almost never”. No more. The ninth grade answer the following, respectively: 3.8, 28.3,44.9, 14.8, 8.2.

Now listen carefully. This is the interpretation: From the matrix no.6 it appears that a majority of the pupils, ca. 75%, think that it “always” or “sometimes” is nice at school. This holds irrespective of the level the pupils in question find themselves in. In the 7th some 7 percent think that it always is nice at school, while in the 1st and 9th grade ca. 4 percent say this. Regarding the more negative alternatives “seldom” and “almost never” it appears that 9.3 and 6.5% of the 7th grade pupils answer this, respectively. In 9th grade the corresponding numbers are 14.8% and 8.2%, while those at the 8th level lie between the scores for the 7th and 9th level”.

What is it that the researcher in fact has done here? He says that 75% of the pupils have a good time in schools. Then I say: “70% of the pupils do not have a good time at school”. And I claim the same mathematical level of rationality as the researcher when I maintain this. How can this be? What has he done? How is this material interpreted so that the school politicians might feel good about it? Well, it is interpreted in the following way:

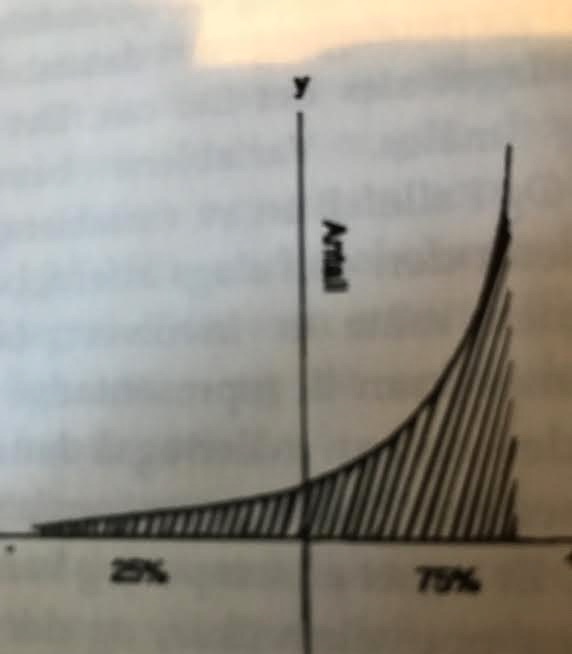

Fig 1.

This is a curve with coordinates regarding attitudes and numbers. Now we have 75% of the answers to the right with the “always good” and “partly good”, and 25% of the answers to the left. That is the negative answers. Such a mathematical curve appears before my inner eyes when I read the interpretations. Is not that so? Seventy-five is of course a very high number, and then it sinks down to twenty-five which describes those who do not like the school very much. But this curve I might invert and say the opposite:

Fig.2

What kind of number is this in reality? What kind of mathematical curve do we get if we read this number? A curve of approximate normal distribution:

Fig. 3

What the numbers show: An approximate normal distribution with twice as many clearly negative as positive.

What do we really know about peoples’ attitudes when we get a Gauss Curve in an investigation of attitudes? What would I get to know if I ask Persian mothers if they would like their children to work 14 hours a day in a weaving workshop that will cripple their hands before they reach 14?…..I assume that we because of the economic situation in the country would get as an answer that some 3.8% of the mothers always like it, 28.3% like it quite often, and so on?

I can refer to another piece of research that shows that when the pupils answer a question of whether they like school or not, the answer may perhaps depend on who is perceived as a figure of authority in research context. The context always plays a role, but is not possible to delimit as an experiment, and is not possible to ascertain through an instrument of investigation (Blichfeldt,1973).

You speak about generalizations, but as you understand through the last example one may go quite astray using information which is assumed to be useful for generalizations. Apart from this, statistics are often strange. You may have 5.000 stones in a heap and you may compute their average weight and volume. But possibly there is no stone which is equal to the average.

A: Well, I don’t know the research you refer to, so it is difficult for me to object to what you say. But how can you contribute, then?

B: Maybe it is typical that you do not know this research. Most of the written works in social science are probably only read by a small group of people having to read them. Because these contributions must be judged in applying for jobs or advancement, etc., and these people who judge them are probably the only ones who understand what is written there.

You mean to ask me what we can contribute with by way of method? I admit that we neither have come so far, but mainly our point of departure is different. Our goal is not primarily to reach the basic and eternal truth. I am in serious doubt whether it exists at all. We are rather on the look for how to initiate a process of learning, and think that the researchers are not, at least not primarily, the ones whom we expect to learn something, for example in schools. We seek to establish a collaboration with those who find themselves in the actual situation, and we try to find ways that permit the participants to define their own premises so that they themselves may define what to do.

A: Sounds nice but reminds me of educational development work rather than research proper.

B: It might be so that development work is part of a research project. When you don`t see the research side of this, it might indicate different ways of understanding what “research” is about in different contexts.

We regard research as a way of learning. How to define learning is not easy. It does anyway imply some change in a system, in an organization etc. In our traditional educational system, learning quite often has been understood as remembering and recalling some specific content. In our understanding, learning is more tied up with inquiries into a problem, to find out how it works, enabling people to solve it, to maintain, repair or change.

When working in an organisation which is a school, those who maintain, mend or change, are the people doing the daily work in classrooms. They are owners of problems and possibilities in this particular workplace, they are the ones who will go on living with them.

Researchers come on short visits and withdraw after a while. This being the case, it is important to involve those doing the daily work in learning processes; to be part of analyses and suggestions.

As researchers we might exclusively design an experiment. The results might indicate that a certain solution of given problems is “good.” (We might even sell it in to be mandatory decided by political administration). Then the exiting and interesting part of the learning process is being reserved for the researchers only. We are most likely the ones who have learned something. Most likely we also have strengthened the traditional dependency workers have on experts and administration.

By involving daily workers, we might, if lucky, attain two important things: Firstly, that those living and working in the organisation learn to inquire and do research into problems themselves without being dependent on experts. Secondly, I believe we might get more accurate or valid knowledge about important characteristics of the particular workplace – than we might get by questionnaires and quantified data only.

A: What you said last, I don`t understand. How can you get more accurate, or valid data when firstly: by necessity you operate on a small sample? Secondly: When you do not start with a definition of the problem to be systematically tested? You need a bigger sample and rigid systematics to use a test of significance for verification. This is how reliability might be attained and valid conclusions drawn.

B: A test of significance is used as a help if a population cannot be observed directly. You need to draw a sample to observe. The test helps you to draw conclusions from the observed sample to the unobserved population. A (statistical) level of significance can, however, not assert if your hypotheses is right or reliable. You define a level of significance at the outset to decide whether you will reject a “null-hypotheses” or not. That is – to which extent your answers and results are random and following a normal distribution-curve. If your findings do not seem random, you might go on working on your hypotheses. Significance is not a general measure of reliability but indicates that a new test under similar conditions might give a similar result.

Now: If you had two inquiries, or questionnaires, one with a sample of 100 and one with a sample of 1000, both with p- level for significance saying 0.05. Which one would you would you trust the most?

A: The inquiry with the large sample.

B: That is wrong. Tests of significance imply control for the size of samples. And we know that chances for rejecting the null-hypotheses are smaller with a small sample. If we have the same p-value in a small sample, it might indicate more deviation from the null-hypotheses in a population. (Rosenthal and Gaito 1963).

A: But it seems self-evident that information from many might be more reliable than from a few. If you had 100 persons in a national category constituting the whole universe to be inquired, it would be more assertive to have information from all of them rather than a sample of 10.

B: Well, if everyone in a category- the whole universe were to be asked, it would of course be more reliable than if only asking a few. But if you ask everyone, the test of significance has no place in your setup. It is only used on samples. For practical purposes we mostly deal with small samples. More single observations are better than few – if you aim at inferring some general insights. Using a test of significance, your sample functions as a single observation. If your sample is increased, you have only made your single observation more voluminous. Which does not necessarily increase reliability. In fact, you might more easily reject the null-hypotheses, also for dubious reasons. (Bakan 1967).

A: That you might more easily reject the null-hypotheses with a bigger sample is right, but don`t come tell me that you know the mathematical basis for tests of significance?

B: No, in that regard I`m alas bluffing as much as most social scientists. I don`t know too much about statistics. What I`ve read and believe to have understood, has mostly triggered some doubt.

A: Ok – let`s go back to the small samples. How do you find that your work with few people who might also influence the research process in ways not defined or predicted could give more reliable or valid knowledge? That is really what you said before we got lost in tests of significance and p-values?

B: When we intend to study something, or even measure something, it is important that our choice of methods is aligned with basic qualities inherent in what we study. If measuring milk, and milk is a liquid, it makes better sense to measure it by cubics, eventually by weight. It does not make sense to measure by meters.

I´d say that fundamental qualities when it comes to human relations, as we are dealing with here, are motions, change. We change and are changed continuously. Patterns and structures, contexts we move within slide apart, tend to dissolve, new patterns evolving. Many changes are imbued with uncertainty and unpredictability. Only simple relations are predictive, and we know what will happen. The territory or stuff we deal with is very complicated and hard to map. It appears different all the time, it is talking back redefining itself. To map such a territory based on standard, static or permanent measures, must be wrong. At the best it might be right for a short while or in some narrowly defined settings.

The accuracy of canon-firing from military vessels was greatly increased when a continuous-aim firing was introduced. A young officer found a method making it possible to keep a stable eye on the sight when both your ship and the enemy were in continuous movement. At first he got negative response from the authorities. They insisted on testing the new firearm on firm ground, narrowly and statically placed. It did not work. (Schön 1971). Well – that was kind of a digressive association – the main idea being that we all the time must look for new ways to systematize, to learn. Ways that to a larger extent take movement and feed-back into consideration.

A: Well..movement.. I`d say that balance and equilibrium is as basic for interpersonal relations as movement, a certain stability. It cannot be right that what you call human or human interrelations appear differently all the time. If that be the case, we had to start learning from scratch all the time. We would not be able to accumulate knowledge – which we in fact do.

B: I think I´d rather say that: as a counterpart to basic movement and change we tend to look for order and stability. With all our might we try to counteract the basic tendency for patterns to dissolve and change. The typical is not patterns being stable, but that they inevitably are messed up and redesigned circumstances. Communication, family-patterns, schools and military forces, are not identical with what they were 15 years ago. Some characteristics evidently remain similar though. (They are still schools, families and armed forces).

I think we are up to a dynamic interchange between movement and attempts to create equilibrium.

I´m not so sure if knowledge is cumulative. Maybe knowledge might be piled up along one dimension or paradigm to a certain point. Then – to deal with paradoxes and disagreements that inevitably occur, there is a need for a qualitative leap; to think along new dimensions to adapt and survive. The “old paradigm of knowledge” seems a dead end. It might be useful to know about it, to avoid or replace it rather than keep piling it up. I might at best represent one among of many ways of knowing.

A: Big words are passing by, but I don´t see how these lofty abstractions are linked to the soft methods you practise.

B: As I said, we haven´t come too far. My reasoning so far is kind of negative, pointing to shortcomings in ordinary use of quantitative methods.

What you might achieve with “soft” methods is to take into consideration movement, change and process. You move together with a field that is always dynamic and moving.

Practically you might enable this, starting by observing or taking part in relevant work-operations. What is experienced is described systematically in a small note brought back to those who do this work – for comments and discussions. Does what you have noted fit their experiences and knowledge? What has been misunderstood, what can be of further use?

By discussing this you might get good corrections. We have reasons to believe the insights you get are fairly valid and relevant at least for the limited group being observed to begin with.

I should add that participant observations and interviews rarely are sufficient. It is important to look into the history of the organisations, into economic, material and formal structures; the framework for jobs done in the group. To quite some extent this also implies the use of statistics available etc.

A: But so far you talk about the registration or description of a situation as it appears. You don´t talk about the dynamics, the moving and the changing that I understood as basic in what you said before.

B: My point so far has been to indicate that methods used to understand an organisation in a given situation must be open and flexible enough to identify or map some of its basic tasks and characteristics. The process of mapping should be shared by the employees, and thus give a possible platform for further change processes. In a school involving teachers and administrative staff.

For all practical purposes, before any mapping is done, you usually start out with an agreement on intentions for the study, stating some general criteria of directions of change in the organisation. Already in discussions of criteria, patterns of organisation and design of work might appear. Quite often as general problems to be understood and solved.

Next step in a process might be to define areas to do practical experiments to improve teaching in a direction agreed upon; transparent and fairly controllable to the participants. In a school they might f.i. want to set the schedule aside for a period to enable work with interdisciplinary tasks, to regroup teachers and pupils. A smaller group of teachers might be given a more overall responsibility for a group of pupils etc. Experiences are registered, discussed and analysed. Quite often patterns in the old organization are better understood once they are transcended. One might identify obstacles or problems in different levels of the organization, rules and prescriptions given locally or centrally. Through the practical experiments they might get hold of an organization able to continuously learn and change itself.

A: Well, I might have three questions to your statements: Two are methodological, and one of a more practical kind. Firstly: When initiating small experiments by changing ways of working or organizing, the validity of outcomes is heavily influenced by the way you go about the whole thing? You get what is known as the “Hawthorne-effect” where a positive outcome is implied in launching the experiment in itself. Secondly: How do you register experiences and findings? Finally: You envisage an organization able to continuously change itself. Thinking of a school, this might rather be seen as a problem than something worth to achieve. I imagine a kind of sisyphus-like setup where the rolling of stones never ends. My impression is that staff of schools rather look for silence and order rather than continuous change.

B: To start with the final question: I believe that Sisyphus has come to stay. No one can stop the moment. Whatever you organize or build will somehow disintegrate. Our fragmentation into written and spoken words to understand something will always be incomplete.

It might even be that the building and constructions is of main interest in itself. Enjoying the final product is passing quickly as an experience. Look at kids building a shack with branches of spruce. When finished, they might play in it for quite a short while, it might be extended or improved for some time. But mostly likely it is soon left or demolished to make something else.

Saying that school staff seem inclined to want order and silence rather than change, I think that this might be due to change often being imposed upon them from above. Imposed by politicians, administration, experts – or some indiscriminate all. My intention is to develop organizations and working conditions enabling teachers to use and develop their own experiences.

You also find the “Hawthorne effect” to invalidate the results. I`d say that this is an effect we are well acquainted with. Rather than understanding it as a source of error and invalidity, we use it for our purpose. What is of general interest is not particular subjects or tasks being used and tried. I don`t believe much in examples of say project tasks being standardized for mass production as teaching blueprints. Of more interest is general criteria of organizing the process, typification of tasks used, how relations between tasks and between the participants involved might be understood.

Registrations might be done by multiple approaches. You might observe as a researcher, teachers and pupils might write small logs of what happens. Together – you and the other participants might analyse and systematize according to the initial criteria agreed upon: Was the outcome satisfactory according to the criteria and direction we aimed at? (Herbst 1970, Fox 1954, Blichfeldt 1975).

Attempts have been done to make frequency analysis based on qualitative data, analysing contents in simple interviews or questionnaires where pre-structuration is kept to a minimum. Here is still much to do. I would hold that traditional quantitative methods well might be used complementary to action research. I already mentioned available general statistics, registration of “hard data” as part of the organizational framework. It is also possible that an action research approach might enable formulation of hypotheses later to be checked by questionnaires. When it comes to methods, I think we always should have complementarity in mind, not to be trapped in hierarchy or reductivity.

Through the final work of systematizing and analysing as a prerequisite for reflection and further planning we are probably closest to mainstream research.

First then we have the research involving teachers and pupils performed locally. Reflections of a more theoretical kind, attempts to understand processes and findings in a larger context is mostly what researchers are paid to do. This part of the work is a large bulk also in an action research project. Teachers (and pupils) mostly have too little space for such efforts.

A: You keep the most interesting part for yourself then. When it adds up you are the one doing the real thinking here?

B: I admit that you deal with a soft point. In principle we do not want to arrive as “experts” in a participative project as said before. But often we are, as “specialists” confronted with expectations to deliver some blueprint or recipe to solutions, to what to do, how and when. I once experienced that a project was cancelled, due to such expectations when discussing intentions: Administration and staff kind of said that: “We would very much like to take part in experiment with new ways of working and organizing. Just tell us precisely what to do, and we will do it.” It never came to their mind that they should take part in defining what to do and how. Even if that was what we tried to tell them. It might be difficult to start a participative project. A fellow action researcher (Rolf Haugen) once said that “starting an action research project is kind of entering the water without making ripples.” And if you succeed, the participants eventually hardly notice your presence.

The role of the researcher might thus be seemingly passive. As when you are invited to describe a project where the initiative as well as definition of tasks and performance of processes stays with the school and its staff. They are the owners. It still gives you an opportunity to learn a lot. Maybe you can contribute some to the local understanding, maybe a new theory of their own doings. Enabling them to have a better grip on how to go on.

Sometimes you might take more initiative, invite discussions – throw in ideas. Then you risk that, maybe enthusiastic on your own ideas, dominate too much, sliding into the role of the expert. The audience might be nodding and accepting, doing whatever you suggest. Or the lot might passively, maybe even reluctant go along, following some colleagues having been fired up. You might end pulling the weight yourself, the whole project resting on your presence. The staff might not get the chance to build their own experiences, ability and self-confidence, but rather to be dependent on you. When the project finishes and you leave, the whole process might come to a halt.

A: Maybe the earthy, social yet independent person in the self-developing organization turns out to be a kind of fiction? After all “ordnung muss sein”? That the ordinary staff member don´t want to or has energy for all this inquiry, involvement and development; would rather stick to some plain routines?

B: Maybe. Maybe also our modern society stimulate the readymade, tailored. Inviting for a fairly irresponsible attitude: “I don´t care.” No, I really don´t think so. Rather I tend to believe there is a “researcher” in everyone – also those not making research for a living. Look at kids, how they investigate, pull apart and construct – again and anew until their curiosity somehow is killed. Which happens alarmingly quickly.

I had some students once looking into contexts and possibilities for children´s playing in a new suburb. They talked to a group of kids 11-12 years old playing on a playground neatly designed. The playground was situated in the outskirts of an available forest area. The kids were asked if they often went to the woods to play? You know what they answered?

“No – because there is no apparatus there for playing.” Sic transit gloria mundi.

In a way I believe that all can do research, and should be given the opportunity to practise it. That organizations should have some leeway that all, also pupils in schools, can preserve and grow their drive to investigate, be curious. To find patterns and connections, make things work. To support the confidence in achieving, to share and be responsible together.

This is not contrary to disciplinary and professional research. There is always a need for someone to systematize, generalize experiences, to find correlations and to investigate in depth defined problem-areas.

We have a lot to learn when it comes to avoiding dependency on experts or hierarchic-bureaucratic leaders. We still need support and framework. We´d like to work more with relations in networks, direct connections between and across work-levels making use of good experiences. Networks that also could minimize dependency on researchers, make it simpler to withdraw, changing roles.

To sum up: Action research might deepen innovation and understanding in social sciences as a complementary methodological approach. Traditional research does not deliver what it promises. We cannot keep only refining existing techniques and approaches. Too often they seem to imply doubtful regular “measures of temperature,” like polls in different areas. I don`t quite see their practical or rational use.

- An action research approach enables me to move better together with a field that is always moving.

- In doing so, I`m being forced to some realism, “down to earth,” to an interchange between practise and theory.

- What we get to know about an organization, about processes hopefully become more valid and reliable. And again: as complementary to other ways of getting to know, not necessary as opposed to them.

- The approach might provide a better basis for learning in an organization, implying that the staff understand their workplace better. That it becomes more transparent and able to be controlled and developed by them. We might say that the approach might be aligned with a democratic idea of participation and influence.

Litt.

Bakan, D (1967): On Method. Jossey Bass, San Francisco.

Bateson, G (1972): Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Ballantine. N.Y.

Blichfeldt, J.F (1973): Om å undersøke skoleelevers holdning til skolen. Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning. nr. 2 1973.

Blichfeldt, J.F (1975): Skole møter skole. Tanum

Blichfeldt, J.F (1976): Sandvens Projectometry. Pedagogen nr. 1

Clark, P.A (1972): Action Research. Harper & Row. N.Y.

Fox, D.J(1954): The research process in education. Psychological Bulletin. Vol.131 no 4 p.327

Herbst, P.G.(1970): Behavioural Worlds. The study of single cases. Tavistock London.

Kuhn, T (1962): The structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago. Chicago-

Rosenthal, R and Gaito, J (1969): The interpretation of Levels of Significance by Psychological Researchers. Journal of Psychology. 55(1) 33-38.

Sandven, J (1975): Projectometry. Universitetsforlaget. Oslo

Spencer-Brown, G (1969): Laws of Form. Allen & Unwin, London.

Schön, D (1971): Beyond the Stable State. Penguin.

Viken, P (1973): Kommentar. I Tiller (red): Barns vilkår i Norge. Et seminar om forskning, praksis og administrasjon. INAS 1973-74